A brave mother tells Michelle Stainistreet of her 16-year fight after her child was misdiagnosed as being autistic.

April 11, 2004

Michelle Stainistreet, Sunday Express (London)

DR. CHERI FLORANCE knew that her son Whitney was different from the moment he was born. Despite expert assurances that he was “perfect,” her maternal instincts told her otherwise. Whitney was unresponsive and his quietness seemed disturbingly unnatural.

Some time later came the diagnosis that seemed to predict a life sentence of isolation and underachievement. Her third child had severe autism. “It was a devastating blow,” she says, “I wasn’t just lonely, I was profoundly sad.”

“When you carry a child for nine months and look forward to loving him and he doesn’t love you back, it breaks your heart; Whitney felt nothing for me for many years. My other kids were like part of me but my dog reacted better to me than Whitney.”

Her son’s birth in 1986 was the start of a 16-year battle, during which she fought to keep her family and her emotions together. “At the time I wasn’t sure we’d make it,” says Cheri, who lives in Ohio. “Our daily schedule was relentless. Making sure Whitney was safe and wasn’t doing something dangerous to himself or his brother and sister was exhausting. The worst thing was the sleep deprivation. Whitney would stay up all night and fall asleep in the afternoon. At night, I’d sit crying, watching the laundry spin round.”

Yet somehow Cheri, 55, coped – despite holding down a pressured job as a world-renowned communications expert and ensuring Whitney, his sister Vanessa and brother William had all the attention they needed. “I couldn’t cope with the idea of Whitney living in a residential home. That gave me strength to go on.”

In her memoir, A Boy Beyond Reach, Cheri describes in touching detail the agonizing journey taken by her family to help Whitney escape a bleak future—an experience she describes as “a complex whirl of heartbreak and joy.”

Despite her profession and links with doctors and educationalists, Cheri had no support in her attempts to help Whitney achieve his potential. Indeed she had a hard job convincing anyone he had any potential.

“They thought I was just a mother, seeing things in a very bizarre way. I was convinced Whitney could think but couldn’t communicate with us and that was causing him so much frustration. They saw someone who was profoundly disabled and who’d never be able to connect with us.”

She vowed to “will” autism – if that was what Whitney had—out of her son.

The profoundly deaf boy had “meltdowns” in which he would bang his head on the floor, bite and urinate on those who got in his way. His phenomenal curiosity and lack of fear would lead him into danger. Often only sheer luck saved him from being maimed or killed.

Cheri says: “I lost count of the times he opened a window and got on the roof, or ran out in the street in the middle of the night. He seemed to have an insatiable curiosity.”

Vanessa and William, now both at university in New York, were supportive and understanding, instead of resenting the time their mother had to devote to their brother, they helped to share the load. When her marriage crumbled, their help was a great support Cheri.

“Now, I look back with great relief that all my children are doing well. So many people told me Whitney would destroy my other two, that I was being selfish by not putting him in a residential home and focusing on Vanessa and William. But they helped him, It was tough but they’re doing great.”

As time went on, Cheri became convinced Whitney’s condition had been wrongly diagnosed. She believed he had an acute communication disorder but had such a high visual system; it was stopping his speaking and listening systems from working properly.

“Whitney couldn’t hear. He had no idea there was language. He couldn’t hear if we screamed in his ear but I could see he was thinking, in a video way.” A breakthrough came when, after working with picture and word cards, Whitney produced a picture of French fries when he was hungry.

Then, when he was seven, Cheri heard a strange voice yell: “Dr. Florance!” They were Whitney’s first words. She recalls: “A door had been unlocked. Once he became fluent in language, the rest of the world made more sense. It took a long time but since then Whitney had gone from strength to strength.”

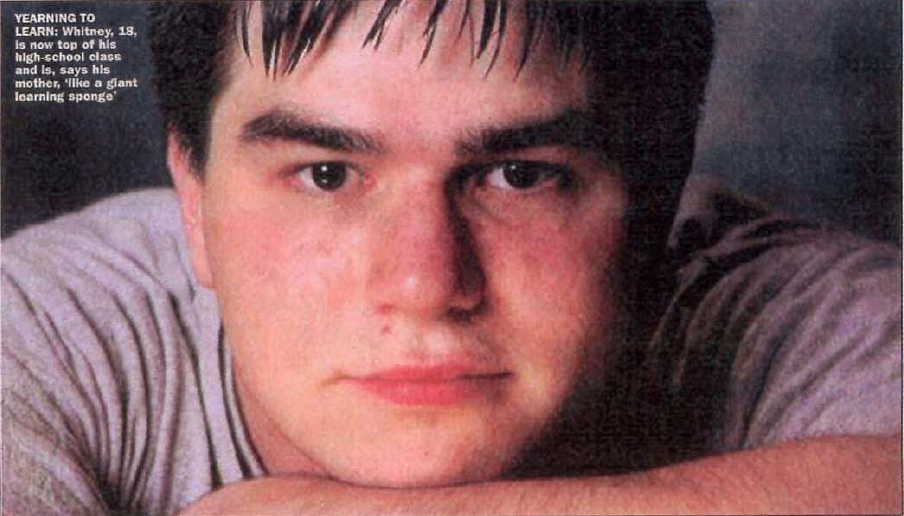

Now 18, he is top of his high school class and on the football team. Cheri describes him as “a giant sponge for learning”.

The transformation led to a family debate about whether writing the book was a good move for Cheri. “It was a big decision. Whitney is now symptom-free. No one really needs to know what he was like as a little boy. Whitney himself didn’t want to read the book. He didn’t want to remember himself as so impaired but he was happy for us to go ahead. Now, he is excited that others are getting help. His was the worst case I’ve seen, so his success is inspirational to others whose cases seem hopeless.”

Her desire to help Whitney re-engineer his brain led Cheri to shift career and set up the Brain Centre to help those with problems like her son’s. She said: “I wanted to find as many like Whitney as I could. I thought it would help me to help him get better and it did.

“What shocked me is how many highly visual people have been tragically misdiagnosed and lumped into other categories. It’s an epidemic—thousands have been let down. We’ve taken a group of our brightest and boldest and are destroying them. I came very close to losing my son over this.”

Meanwhile, she is enjoying watching her son enjoy life as a “normal” young man and having more time to spend on herself. She says: “I’ve finished a journey. I’m learning sculpture, working out—and I have the leisure of spending time with Whitney. “

Cheri believes her work has led her to identify a communications disorder—routinely misdiagnosed as autism or Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD)—which she has dubbed the Florance Maverick Syndrome. Her experience has made her determined to help other mothers avoid the torment she went through.

Meanwhile, she is enjoying watching her son enjoy life as a “normal” young man and having more time to spend on herself. She says: “I’ve finished a journey. I’m learning sculpture, working out—and I have the leisure of spending time with Whitney.“

If she is right and the brains of children with psychiatric disorders can be “re-engineered,” if the underlying disability can be fixed, Cheri’s approach could help many thousands worldwide. She is considering opening another Brain Clinic in Britain later this year.

“He flunked out of autism school and was put in the county’s program for the unteachable, yet there he was this morning debating philosophy with me, talking about whether there’s a brain and a mind or just a brain.”

“As I watched him leave and drive off to high school I could have cried. I thought: I’ll never take this for granted.”

For a copy of A Boy Beyond Reach, published by Simon & Schuster, and for more information about the Florance Maverick Syndrome, log on to www.cheriflorance.com.